It would be impossible to visit or live in Indonesia and not be exposed to one of the country's most highly developed art forms, batik. On your first visit to a batik store or factory you will undoubtedly experience an overwhelming stimulation of the senses - due to the many colors, patterns and the actual smell of batik. Only through repeated visits and a bit of study will the types of designs and their origins become apparent.

The word batik is thought to be derived from the word 'ambatik' which translated means 'a cloth with little dots'. The suffix 'tik' means little dot, drop, point or to make dots. Batik may also originate from the Javanese word 'tritik' which describes a resist process for dying where the patterns are reserved on the textiles by tying and sewing areas prior to dying, similar to tie dye techniques. Another Javanese phase for the mystical experience of making batik is “mbatik manah” which means “drawing a batik design on the heart”.

A Brief History

Although experts disagree as to the precise origins of batik, samples of dye resistance patterns on cloth can be traced back 1,500 years ago to Egypt and the Middle East. Samples have also been found in Turkey, India, China, Japan and West Africa from past centuries. Although in these countries people were using the technique of dye resisting decoration, within the textile realm, none have developed batik to its present day art form as the highly developed intricate batik found on the island of Java in Indonesia.

Although there is mention of 'fabrics highly decorated' in Dutch transcripts from the 17th century, most scholars believe that the intricate Javanese batik designs would only have been possible after the importation of finely woven imported cloth, which was first imported to Indonesia from India around the 1800s and afterwards from Europe beginning in 1815. Textile patterns can be seen on stone statues that are carved on the walls of ancient Javanese temples such as Prambanan (AD 800), however there is no conclusive evidence that the cloth is batik. It could possibly be a pattern that was produced with weaving techniques and not dying. What is clear is that in the 19th century batik became highly developed and was well ingrained in Javanese cultural life.

Although there is mention of 'fabrics highly decorated' in Dutch transcripts from the 17th century, most scholars believe that the intricate Javanese batik designs would only have been possible after the importation of finely woven imported cloth, which was first imported to Indonesia from India around the 1800s and afterwards from Europe beginning in 1815. Textile patterns can be seen on stone statues that are carved on the walls of ancient Javanese temples such as Prambanan (AD 800), however there is no conclusive evidence that the cloth is batik. It could possibly be a pattern that was produced with weaving techniques and not dying. What is clear is that in the 19th century batik became highly developed and was well ingrained in Javanese cultural life.

Some experts feel that batik was originally reserved as an art form for Javanese royalty. Certainly it's royal nature was clear as certain patterns were reserved to be worn only by royalty from the Sultan's palace. Princesses and noble women may have provided the inspiration for the highly refined design sense evident in traditional patterns. It is highly unlikely though that they would be involved in any more than the first wax application. Most likely, the messy work of dyeing and subsequent waxings was left to court artisans who would work under their supervision.

Javanese royalty were known to be great patrons of the arts and provided the support necessary to develop many art forms, such as silver ornamentation, wayang kulit (leather puppets) and gamelan orchestras. In some cases the art forms overlap. The Javanese dalang (puppeteer) not only was responsible for the wayang puppets but was also  an important source of batik patterns. Wayang puppets are usually made of goat skin, which is then perforated and painted to create the illusion of clothing on the puppet. Used puppets were often sold to eager ladies who used the puppets as guides for their batik patterns. They would blow charcoal through the holes that define the patterns of clothing on the puppets, in order to copy the intricate designs onto the cloth.

an important source of batik patterns. Wayang puppets are usually made of goat skin, which is then perforated and painted to create the illusion of clothing on the puppet. Used puppets were often sold to eager ladies who used the puppets as guides for their batik patterns. They would blow charcoal through the holes that define the patterns of clothing on the puppets, in order to copy the intricate designs onto the cloth.

Other scholars disagree that batik was only reserved as an art form for royalty, as they also feel its use was prevalent with the rakyat, the people. It was regarded an important part of a young ladies accomplishment that she be capable of handling a canting (the pen-like instrument used to apply wax to the cloth) with a reasonable amount of skill, certainly as important as cookery and other housewifery arts to Central Javanese women.

Selection and Preparation of the Cloth for Batik

Natural materials such as cotton or silk are used for the cloth, so that it can absorb the wax that is applied in the dye resisting process. The fabrics must be of a high thread count (densely woven). It is important that cloth of high quality have this high thread count so that the intricate design qualities of batik can be maintained.

The cloth that is used for batik is washed and boiled in water many times prior to the application of wax so that all traces of starches, lime, chalk and other sizing materials are removed. Prior to the implementation of modern day techniques, the cloth would have been pounded with a wooden mallet or ironed to make it smooth and supple so it could best receive the wax design. With the finer machine-made cotton available today, the pounding or ironing processes can be omitted. Normally men did this step in the batik process.

The cloth that is used for batik is washed and boiled in water many times prior to the application of wax so that all traces of starches, lime, chalk and other sizing materials are removed. Prior to the implementation of modern day techniques, the cloth would have been pounded with a wooden mallet or ironed to make it smooth and supple so it could best receive the wax design. With the finer machine-made cotton available today, the pounding or ironing processes can be omitted. Normally men did this step in the batik process.

Strict industry standards differentiate the different qualities of the cloth used today, which include Primissima (the best) and Prima. The cloth quality is often written on the edge of the design. A lesser quality cloth which is often used in Blaco.

Batik Design Tools

Although the art form of batik is very intricate, the tools that are used are still very simple. The canting, believed to be a purely Javanese invention, is a small thin wall spouted copper container (sometimes called a wax pen) that is connected to a short bamboo handle. Normally it is approximately 11 cm. in length. The copper container is filled with melted wax and the artisan then uses the canting to draw the design on the cloth.

Canting have different sizes of spouts (numbered to correspond to the size) to achieve varied design effects. The spout can vary from 1 mm in diameter for very fine detailed work to wider spouts used to fill in large design areas. Dots and parallel lines may be drawn with canting that have up to 9 spouts. Sometimes a wad of cotton is fastened over the mouth of the canting or attached to a stick that acts as a brush to fill in very large areas.

For close-up pictures of canting.

Wajan

The wajan is the container that holds the melted wax. It looks like a small wok. Normally it is made of iron or earthenware. The wajan is placed on a small brick charcoal stove or a spirit burner called an 'anglo'. The wax is kept in a melted state while the artisan is applying the wax to the cloth.

The wajan is the container that holds the melted wax. It looks like a small wok. Normally it is made of iron or earthenware. The wajan is placed on a small brick charcoal stove or a spirit burner called an 'anglo'. The wax is kept in a melted state while the artisan is applying the wax to the cloth.

Wax

Different kinds and qualities of wax are used in batik. Common waxes used for batik consist of a mixture of beeswax, used for its malleability, and paraffin, used for its friability. Resins can be added to increase adhesiveness and animal fats create greater liquidity.

The best waxes are from the Indonesian islands of Timor, Sumbawa and Sumatra; three types of petroleum-based paraffin (white, yellow and black) are used. The amounts mixed are measured in grams and vary according to the design. Wax recipes can be very closely guarded secrets. Varying colors of wax make it possible to disguise different parts of the pattern through the various dying stages. Larger areas of the pattern are filled in with wax that is cheaper quality and the higher quality wax is used on the more intricately detailed sections of the design.

The best waxes are from the Indonesian islands of Timor, Sumbawa and Sumatra; three types of petroleum-based paraffin (white, yellow and black) are used. The amounts mixed are measured in grams and vary according to the design. Wax recipes can be very closely guarded secrets. Varying colors of wax make it possible to disguise different parts of the pattern through the various dying stages. Larger areas of the pattern are filled in with wax that is cheaper quality and the higher quality wax is used on the more intricately detailed sections of the design.

The wax must be kept at the proper temperature. A wax that is too cool will clog the spout of the canting. A wax that is too hot will flow too quickly and be uncontrollable. The artisan will often blow into the spout of the canting before applying wax to the cloth in order to clear the canting of any obstructions.

Cap

Creating batik is a very time consuming craft. To meet growing demands and make the fabric more affordable to the masses, in the mid-19th century the . cap. (copper stamp - pronounced chop) was developed. This invention enabled a higher volume of batik production compared to the traditional method which entailed the tedious application of wax by hand with a canting.

Creating batik is a very time consuming craft. To meet growing demands and make the fabric more affordable to the masses, in the mid-19th century the . cap. (copper stamp - pronounced chop) was developed. This invention enabled a higher volume of batik production compared to the traditional method which entailed the tedious application of wax by hand with a canting.

Each cap is a copper block that makes up a design unit. Cap are made of 1.5 cm wide copper stripes that are bent into the shape of the design. Smaller pieces of wire are used for the dots. When complete, the pattern of copper strips is attached to the handle.

The cap must be precisely made. This is especially true if the pattern is to be stamped on both sides of the fabric. It is imperative that both sides of the cap are identical so that pattern will be consistent.

Sometimes cap are welded between two grids like pieces of copper that will make a base for the top and the bottom. The block is cut in half at the center so the pattern on each half is identical. Cap vary in size and shape depending on the pattern they are needed for. It is seldom that a cap will exceed 24 cm in diameter, as this would make the handling too difficult.

bottom. The block is cut in half at the center so the pattern on each half is identical. Cap vary in size and shape depending on the pattern they are needed for. It is seldom that a cap will exceed 24 cm in diameter, as this would make the handling too difficult.

Men usually handle the application of wax using cap. A piece of cloth that involves a complicated design could require as many as ten sets of cap. The usage of cap, as opposed to canting, to apply the wax has reduced the amount of time to make a cloth.

Today, batik quality is defined by cap or tulis, the second meaning hand-drawn designs which use a canting, or kombinasi, a combination of the two techniques.

Dyes

Traditional colors for Central Javanese batik were made from natural ingredients and consisted primarily of beige, blue, brown and black.

The oldest color that was used in traditional batik making was blue. The color was made from the leaves of the Indigo plant. The leaves were mixed with molasses sugar and lime and left to stand overnight. Sometimes sap from the Tinggi tree was added to act as a fixing agent. Lighter blue was achieved by leaving the cloth in the dye bath for short periods of time. For darker colors, the cloth would be left in the dye bath for days and may have been submerged up to 8 - 10 times a day.

In traditional batik, the second color applied was a brown color called soga. The color could range from light yellow to a dark brown. The dye came from the bark of the Soga tree. Another color that was traditionally used was a dark red color called mengkuda. This dye was created from the leaves of the Morinda Citrifolia.

The final hue depended on how long the cloth was soaked in the dye bath and how often it was dipped. Skilled artisans can create many variations of these traditional colors. Aside from blue, green would be achieved by mixing blue with yellow; purple was obtained by mixing blue and red. The soga brown color mixed with indigo would produce a dark blue-black color.

Design Process

The outline of the pattern is blocked out onto the cloth, traditionally with charcoal or graphite. Traditional batik designs utilize patterns handed down over the generations. It is very seldom that an artisan is so skilled that he can work from memory and would not need to draw an outline of the pattern before applying the wax. Often designs are traced from stencils or patterns called pola. Another method of tracing a pattern onto a cloth is by laying the cloth on a glass table that is illuminated from below which casts a shadow of the pattern onto the cloth. The shadow is then traced with a pencil. In large batik factories today, men usually are in charge of drawing the patterns onto the cloth. Click here to see the step-by-step process of making batik.

Waxing

Once the design is drawn out onto the cloth it is then ready to be waxed. Wax is applied to the cloth over the areas  of the design that the artisan wishes to remain the original color of the cloth. Normally this is white or cream.

of the design that the artisan wishes to remain the original color of the cloth. Normally this is white or cream.

Female workers sit on a low stool or on a mat to apply the wax with a canting. The fabric that they are working on is draped over light bamboo frames called gawangan to allow the freshly applied wax to cool and harden. The wax is heated in the wajan until it is of the desired consistency. The artisan then dips her canting into the wax to fill the bowl of the canting.

Artisans use the wax to retrace the pencil outline on the fabric. A small drop cloth is kept on the woman. s lap to protect her from hot dripping wax. The stem of the canting is held with the right hand in a horizontal position to prevent any accidental spillage, which greatly reduces the value of the final cloth. The left hand is placed behind the fabric for support. The spout does not touch the fabric, but it held just above the area the artisan is working on. To ensure the pattern is well defined, batik is waxed on both sides. True tulis batik is reversible, as the pattern should be identical on both sides.

The most experienced artisans normally do first waxings. Filling in of large areas may be entrusted to less experienced artisans. Mistakes are very difficult to correct. If wax is accidentally spilt on the cloth, the artisan will try to remove the unwanted wax by sponging it with hot water. Then a heated iron rod with a curved end is used to try and lift off the remaining wax. Spilled wax can never be completely removed so it is imperative that the artisans are very careful.

If the cap method is utilized, this procedure is normally done by men. The cap are dipped into melted wax. Just under the surface of the melted wax is a folded cloth approximately 30 centimeters square. When this cloth is saturated with wax it acts like a stamp pad. The cap is pressed into the fabric until the design side of the cap is coated with wax. The saturated cap is then stamped onto the fabric, leaving the design of the cap. This process is repeated until the entire cloth is covered. Often cap and canting methods are combined on the same piece of cloth.

If the cap method is utilized, this procedure is normally done by men. The cap are dipped into melted wax. Just under the surface of the melted wax is a folded cloth approximately 30 centimeters square. When this cloth is saturated with wax it acts like a stamp pad. The cap is pressed into the fabric until the design side of the cap is coated with wax. The saturated cap is then stamped onto the fabric, leaving the design of the cap. This process is repeated until the entire cloth is covered. Often cap and canting methods are combined on the same piece of cloth.

Better quality batik may be waxed utilizing canting in one part of Indonesia and then sent to another part of Indonesia where the cap part of the process is completed. On better quality cap fabric great care is taken to match the pattern exactly. Lower grade batik is characterized by overlapping lines or lightened colored lines indicating the cap was not applied correctly.

Dyeing

After the initial wax has been applied, the fabric is ready for the first dye bath. Traditionally dying was done in earthenware tubs. Today most batik factories use large concrete vats. Above the vats are ropes with pulleys that the fabric is draped over after it has been dipped into the dye bath.

The waxed fabric is immersed in the dye bath of the first color. The amount of time it is left in the bath determines the hue of the color; darker colors require longer periods or numerous immersions. The fabric is then put into a cold water bath to harden the wax.

When the desired color has been achieved and the fabric has dried, wax is reapplied over the areas that the artisan wishes to maintain the first dye color or another color at a later stage in the dying process.

When the desired color has been achieved and the fabric has dried, wax is reapplied over the areas that the artisan wishes to maintain the first dye color or another color at a later stage in the dying process.

When an area that has been covered with wax previously needs to be exposed so that it can be dyed, the applied wax is scraped away with a small knife. The area is then sponged with hot water and resized with rice starch before it is re-immersed in the subsequent dye bath.

If a marble effect is desired, the wax is intentionally cracked before being placed in the dye bath. The dye seeps into the tiny cracks that create the fine lines that are characteristic of batik. Traditionally, cracks were a sign of inferior cloth especially on indigo color batik. On brown batik, however, the marble effect was accepted.

The number of colors in batik represents how many times it was immersed in the dye bath and how many times wax had to be applied and removed. A multicolored batik represents a lot more work that a single or two-color piece. Numerous dye processes are usually reflected in the price of the cloth. Nowadays, chemical dyes have pretty much replaced traditional dyes, so colors are endless and much more liberally used.

Special Treatments to the Batik Cloth

Prada or Gold Cloth

For special occasions, batik was formerly decorated with gold lead or gold dust. This cloth is known as Prada cloth. Gold leaf was used in the Jogjakarta and Surakarta area. The Central Javanese used gold dust to decorate their Prada cloth. It was applied to the fabric using a handmade glue consisting of egg white or linseed oil and yellow earth. The gold would remain on the cloth even after it had been washed. The gold could follow the design of the cloth or could take on its own design. Older batiks could be given a new look by applying gold to them. Gold decorated cloth is still made today; however, gold paint has replaced gold dust and leaf.

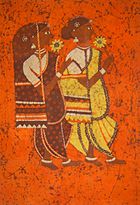

Batik Designs

Although there are thousands of different batik designs, particular designs have traditionally been associated with traditional festivals and specific religious ceremonies. Previously, it was thought that certain cloth had mystical powers to ward off ill fortune, while other pieces could bring good luck.

Certain batik designs are reserved for brides and bridegrooms as well as their families. Other designs are reserved for the Sultan and his family or their attendants. A person's rank could be determined by the pattern of the batik he/she wore.

In general, there are two categories of batik design: geometric motifs (which tend to be the earlier designs) and free form designs, which are based on stylized patterns of natural forms or imitations of a woven texture. Nitik is the most famous design illustrating this effect.

Certain areas are known for a predominance of certain designs. Central Javanese designs are influenced by traditional patterns and colors. Batik from the north coast of Java, near Pekalongan and Cirebon, have been greatly influenced by Chinese culture and effect brighter colors and more intricate flower and cloud designs.

High fashion designs drawn on silk are very popular with wealthy Indonesians. These exceptionally high-quality pieces can take months to create and costs hundreds of dollars.

Kawung

Kawung is another very old design consisting of intersecting circles, known in Java since at least the thirteenth century. This design has appeared carved into the walls of many temples throughout Java such as Prambanan near Jogjakarta and Kediri in East Java. For many years, this pattern was reserved for the royal court of the Sultan of Jogjakarta. The circles are sometimes embellished inside with two or more small crosses or other ornaments such as intersecting lines or dots. It has been suggested that the ovals might represent flora such as the fruit of the kapok (silk cotton) tree or the aren (sugar palm).

Kawung is another very old design consisting of intersecting circles, known in Java since at least the thirteenth century. This design has appeared carved into the walls of many temples throughout Java such as Prambanan near Jogjakarta and Kediri in East Java. For many years, this pattern was reserved for the royal court of the Sultan of Jogjakarta. The circles are sometimes embellished inside with two or more small crosses or other ornaments such as intersecting lines or dots. It has been suggested that the ovals might represent flora such as the fruit of the kapok (silk cotton) tree or the aren (sugar palm).

Ceplok

Ceplok is a general name for a whole series of geometric designs based on squares, rhombs, circles, stars, etc. Although fundamentally geometric, ceplok can also represent abstractions and stylization of flowers, buds, seeds and even animals. Variations in color intensity can create illusions of depth and the overall effect is not unlike medallion patterns seen on Turkish tribal rugs. The Indonesian population is largely Muslim, a religion that forbids the portrayal of animal and human forms in a realistic manner. To get around this prohibition, the batik worker does not attempt to express this matter in a realistic form. A single element of the form is chosen and then that element is repeated again and again in the pattern.

Ceplok is a general name for a whole series of geometric designs based on squares, rhombs, circles, stars, etc. Although fundamentally geometric, ceplok can also represent abstractions and stylization of flowers, buds, seeds and even animals. Variations in color intensity can create illusions of depth and the overall effect is not unlike medallion patterns seen on Turkish tribal rugs. The Indonesian population is largely Muslim, a religion that forbids the portrayal of animal and human forms in a realistic manner. To get around this prohibition, the batik worker does not attempt to express this matter in a realistic form. A single element of the form is chosen and then that element is repeated again and again in the pattern.

Parang

Parang was once used exclusively by the royal courts of Central Java. It has several suggested meanings such as 'rugged rock', 'knife pattern' or 'broken blade'. The Parang design consists of slanting rows of thick knife-like segments running in parallel diagonal bands. Parang usually alternated with narrower bands in a darker contrasting color. These darker bands contain another design element, a line of lozenge-shaped motifs call mlinjon. There are many variations of this basic striped pattern with its elegant sweeping lines, with over forty parang designs recorded. The most famous is the 'Parang Rusak' which in its most classical form consisting of rows of softly folded parang. This motif also appears in media other than batik, including woodcarving and as ornamentation on gamelan musical instruments.

Parang was once used exclusively by the royal courts of Central Java. It has several suggested meanings such as 'rugged rock', 'knife pattern' or 'broken blade'. The Parang design consists of slanting rows of thick knife-like segments running in parallel diagonal bands. Parang usually alternated with narrower bands in a darker contrasting color. These darker bands contain another design element, a line of lozenge-shaped motifs call mlinjon. There are many variations of this basic striped pattern with its elegant sweeping lines, with over forty parang designs recorded. The most famous is the 'Parang Rusak' which in its most classical form consisting of rows of softly folded parang. This motif also appears in media other than batik, including woodcarving and as ornamentation on gamelan musical instruments.

Washing Batik

Harsh chemical detergents, dryers and drying of fabrics in the sun may fade the colors in batik. Traditionally dyed batiks should be washed in soap for sensitive fabrics, such as Woolite, Silky or Halus. Fine batik in Indonesia is washed with the lerak fruit which can be purchased at most traditional markets. A bottled version of this detergent is also available at batik stores. Be sure to line dry batik in a shady area and not in direct sunlight.

Modern Batik

Modern batik, although having strong ties to traditional batik, utilizes linear treatment of leaves, flowers and birds. These batiks tend to be more dependent on the dictates of the designer rather than the stiff guidelines that have guided traditional craftsmen. This is also apparent in the use of color that modern designers use. Artisans are no  longer dependent on traditional (natural) dyes, as chemical dyes can produce any color that they wish to achieve. Modern batik still utilizes canting and cap to create intricate designs.

longer dependent on traditional (natural) dyes, as chemical dyes can produce any color that they wish to achieve. Modern batik still utilizes canting and cap to create intricate designs.

Fashion designers such as Iwan Tirta have aggressively introduced batik into the world fashion scene. They have done much to promote the Indonesian art of batik dress, in its traditional and modern forms.

The horizon of batik is continuing to widen. While the design process has remained basically the same over the last century, the process shows great progress in recent decades. Traditionally, batik was sold in 2 1/4 meter lengths used for kain panjang or sarong in traditional dress. Now, not only is batik used as a material to clothe the human body, its uses also include furnishing fabrics, heavy canvas wall hangings, tablecloths and household accessories. Batik techniques are used by famous artists to create batik paintings which grace many homes and offices.

Fine quality handmade batik is very expensive and the production of such works is very limited. However, in a  world that is dominated by machines there is an increasing interest in materials that have been handmade. Batik is one of these materials.

world that is dominated by machines there is an increasing interest in materials that have been handmade. Batik is one of these materials.

During your stay in Indonesia, take advantage of your time here to learn more about the fascinating world of batik. Have a batik dress or men's business shirt made for you by a seamstress or tailor. Visit batik factories in Jogjakarta, Surakarta or Pekalongan to see for yourself how the intricate process is conducted or ask questions of batik artisans giving demonstrations in stores such as Sarinah or Pasaraya in Jakarta. You will come away with sense of wonder over the time, effort and patience put into the creation of each batik cloth. You too may soon grow to love the distinctive waxy smell of batik and your batik acquisitions will provide many memories of your stay in Indonesia. Your support of the batik industry will also ensure that this art form grows to even greater peaks.

Indigenous Dress in the Making of a Nation

Indigenous Dress in the Making of a Nation

from her home. Relatives and friends from throughout Java often came to Hartati's home in Jakarta to sell batik through her mother. Throughout her childhood she saw her grandmother, mother and other relatives wearing batik for everyday clothing.

from her home. Relatives and friends from throughout Java often came to Hartati's home in Jakarta to sell batik through her mother. Throughout her childhood she saw her grandmother, mother and other relatives wearing batik for everyday clothing. Lila Noerhayati and Kirono Arundatie - all of whom were also engineers, established Batik Canting in 1998. Each partner specializes in different home accessories, with Hartati creating the wall hangings. The creative synergy of their collaborative efforts has resulted in a truly beautiful one-of-a-kind home accessories shop.

Lila Noerhayati and Kirono Arundatie - all of whom were also engineers, established Batik Canting in 1998. Each partner specializes in different home accessories, with Hartati creating the wall hangings. The creative synergy of their collaborative efforts has resulted in a truly beautiful one-of-a-kind home accessories shop. a skirt-like item of clothing. In the traditional Javanese women's clothing ensemble called kain kebaya, the batik kain is wrapped from the waist around the hips and legs, and worn with a traditional kebaya top.

a skirt-like item of clothing. In the traditional Javanese women's clothing ensemble called kain kebaya, the batik kain is wrapped from the waist around the hips and legs, and worn with a traditional kebaya top. the residential area of Pondok Indah with distinctively Indonesian artifacts, antique ceramic plates, skulls of indigenous deer, paintings and crafts. The open patio at the rear of their home is the setting for the displays of exquisite wall hangings.

the residential area of Pondok Indah with distinctively Indonesian artifacts, antique ceramic plates, skulls of indigenous deer, paintings and crafts. The open patio at the rear of their home is the setting for the displays of exquisite wall hangings. Although there is mention of 'fabrics highly decorated' in Dutch transcripts from the 17th century, most scholars believe that the intricate Javanese batik designs would only have been possible after the importation of finely woven imported cloth, which was first imported to Indonesia from India around the 1800s and afterwards from Europe beginning in 1815. Textile patterns can be seen on stone statues that are carved on the walls of ancient Javanese temples such as Prambanan (AD 800), however there is no conclusive evidence that the cloth is batik. It could possibly be a pattern that was produced with weaving techniques and not dying. What is clear is that in the 19th century batik became highly developed and was well ingrained in Javanese cultural life.

Although there is mention of 'fabrics highly decorated' in Dutch transcripts from the 17th century, most scholars believe that the intricate Javanese batik designs would only have been possible after the importation of finely woven imported cloth, which was first imported to Indonesia from India around the 1800s and afterwards from Europe beginning in 1815. Textile patterns can be seen on stone statues that are carved on the walls of ancient Javanese temples such as Prambanan (AD 800), however there is no conclusive evidence that the cloth is batik. It could possibly be a pattern that was produced with weaving techniques and not dying. What is clear is that in the 19th century batik became highly developed and was well ingrained in Javanese cultural life. an important source of batik patterns. Wayang puppets are usually made of goat skin, which is then perforated and painted to create the illusion of clothing on the puppet. Used puppets were often sold to eager ladies who used the puppets as guides for their batik patterns. They would blow charcoal through the holes that define the patterns of clothing on the puppets, in order to copy the intricate designs onto the cloth.

an important source of batik patterns. Wayang puppets are usually made of goat skin, which is then perforated and painted to create the illusion of clothing on the puppet. Used puppets were often sold to eager ladies who used the puppets as guides for their batik patterns. They would blow charcoal through the holes that define the patterns of clothing on the puppets, in order to copy the intricate designs onto the cloth. The cloth that is used for batik is washed and boiled in water many times prior to the application of wax so that all traces of starches, lime, chalk and other sizing materials are removed. Prior to the implementation of modern day techniques, the cloth would have been pounded with a wooden mallet or ironed to make it smooth and supple so it could best receive the wax design. With the finer machine-made cotton available today, the pounding or ironing processes can be omitted. Normally men did this step in the batik process.

The cloth that is used for batik is washed and boiled in water many times prior to the application of wax so that all traces of starches, lime, chalk and other sizing materials are removed. Prior to the implementation of modern day techniques, the cloth would have been pounded with a wooden mallet or ironed to make it smooth and supple so it could best receive the wax design. With the finer machine-made cotton available today, the pounding or ironing processes can be omitted. Normally men did this step in the batik process. The wajan is the container that holds the melted wax. It looks like a small wok. Normally it is made of iron or earthenware. The wajan is placed on a small brick charcoal stove or a spirit burner called an 'anglo'. The wax is kept in a melted state while the artisan is applying the wax to the cloth.

The wajan is the container that holds the melted wax. It looks like a small wok. Normally it is made of iron or earthenware. The wajan is placed on a small brick charcoal stove or a spirit burner called an 'anglo'. The wax is kept in a melted state while the artisan is applying the wax to the cloth. The best waxes are from the Indonesian islands of Timor, Sumbawa and Sumatra; three types of petroleum-based paraffin (white, yellow and black) are used. The amounts mixed are measured in grams and vary according to the design. Wax recipes can be very closely guarded secrets. Varying colors of wax make it possible to disguise different parts of the pattern through the various dying stages. Larger areas of the pattern are filled in with wax that is cheaper quality and the higher quality wax is used on the more intricately detailed sections of the design.

The best waxes are from the Indonesian islands of Timor, Sumbawa and Sumatra; three types of petroleum-based paraffin (white, yellow and black) are used. The amounts mixed are measured in grams and vary according to the design. Wax recipes can be very closely guarded secrets. Varying colors of wax make it possible to disguise different parts of the pattern through the various dying stages. Larger areas of the pattern are filled in with wax that is cheaper quality and the higher quality wax is used on the more intricately detailed sections of the design. Creating batik is a very time consuming craft. To meet growing demands and make the fabric more affordable to the masses, in the mid-19th century the . cap. (copper stamp - pronounced chop) was developed. This invention enabled a higher volume of batik production compared to the traditional method which entailed the tedious application of wax by hand with a canting.

Creating batik is a very time consuming craft. To meet growing demands and make the fabric more affordable to the masses, in the mid-19th century the . cap. (copper stamp - pronounced chop) was developed. This invention enabled a higher volume of batik production compared to the traditional method which entailed the tedious application of wax by hand with a canting. bottom. The block is cut in half at the center so the pattern on each half is identical. Cap vary in size and shape depending on the pattern they are needed for. It is seldom that a cap will exceed 24 cm in diameter, as this would make the handling too difficult.

bottom. The block is cut in half at the center so the pattern on each half is identical. Cap vary in size and shape depending on the pattern they are needed for. It is seldom that a cap will exceed 24 cm in diameter, as this would make the handling too difficult. of the design that the artisan wishes to remain the original color of the cloth. Normally this is white or cream.

of the design that the artisan wishes to remain the original color of the cloth. Normally this is white or cream. If the cap method is utilized, this procedure is normally done by men. The cap are dipped into melted wax. Just under the surface of the melted wax is a folded cloth approximately 30 centimeters square. When this cloth is saturated with wax it acts like a stamp pad. The cap is pressed into the fabric until the design side of the cap is coated with wax. The saturated cap is then stamped onto the fabric, leaving the design of the cap. This process is repeated until the entire cloth is covered. Often cap and canting methods are combined on the same piece of cloth.

If the cap method is utilized, this procedure is normally done by men. The cap are dipped into melted wax. Just under the surface of the melted wax is a folded cloth approximately 30 centimeters square. When this cloth is saturated with wax it acts like a stamp pad. The cap is pressed into the fabric until the design side of the cap is coated with wax. The saturated cap is then stamped onto the fabric, leaving the design of the cap. This process is repeated until the entire cloth is covered. Often cap and canting methods are combined on the same piece of cloth. When the desired color has been achieved and the fabric has dried, wax is reapplied over the areas that the artisan wishes to maintain the first dye color or another color at a later stage in the dying process.

When the desired color has been achieved and the fabric has dried, wax is reapplied over the areas that the artisan wishes to maintain the first dye color or another color at a later stage in the dying process.

Kawung is another very old design consisting of intersecting circles, known in Java since at least the thirteenth century. This design has appeared carved into the walls of many temples throughout Java such as Prambanan near Jogjakarta and Kediri in East Java. For many years, this pattern was reserved for the royal court of the Sultan of Jogjakarta. The circles are sometimes embellished inside with two or more small crosses or other ornaments such as intersecting lines or dots. It has been suggested that the ovals might represent flora such as the fruit of the kapok (silk cotton) tree or the aren (sugar palm).

Kawung is another very old design consisting of intersecting circles, known in Java since at least the thirteenth century. This design has appeared carved into the walls of many temples throughout Java such as Prambanan near Jogjakarta and Kediri in East Java. For many years, this pattern was reserved for the royal court of the Sultan of Jogjakarta. The circles are sometimes embellished inside with two or more small crosses or other ornaments such as intersecting lines or dots. It has been suggested that the ovals might represent flora such as the fruit of the kapok (silk cotton) tree or the aren (sugar palm). Ceplok is a general name for a whole series of geometric designs based on squares, rhombs, circles, stars, etc. Although fundamentally geometric, ceplok can also represent abstractions and stylization of flowers, buds, seeds and even animals. Variations in color intensity can create illusions of depth and the overall effect is not unlike medallion patterns seen on Turkish tribal rugs. The Indonesian population is largely Muslim, a religion that forbids the portrayal of animal and human forms in a realistic manner. To get around this prohibition, the batik worker does not attempt to express this matter in a realistic form. A single element of the form is chosen and then that element is repeated again and again in the pattern.

Ceplok is a general name for a whole series of geometric designs based on squares, rhombs, circles, stars, etc. Although fundamentally geometric, ceplok can also represent abstractions and stylization of flowers, buds, seeds and even animals. Variations in color intensity can create illusions of depth and the overall effect is not unlike medallion patterns seen on Turkish tribal rugs. The Indonesian population is largely Muslim, a religion that forbids the portrayal of animal and human forms in a realistic manner. To get around this prohibition, the batik worker does not attempt to express this matter in a realistic form. A single element of the form is chosen and then that element is repeated again and again in the pattern. Parang was once used exclusively by the royal courts of Central Java. It has several suggested meanings such as 'rugged rock', 'knife pattern' or 'broken blade'. The Parang design consists of slanting rows of thick knife-like segments running in parallel diagonal bands. Parang usually alternated with narrower bands in a darker contrasting color. These darker bands contain another design element, a line of lozenge-shaped motifs call mlinjon. There are many variations of this basic striped pattern with its elegant sweeping lines, with over forty parang designs recorded. The most famous is the 'Parang Rusak' which in its most classical form consisting of rows of softly folded parang. This motif also appears in media other than batik, including woodcarving and as ornamentation on gamelan musical instruments.

Parang was once used exclusively by the royal courts of Central Java. It has several suggested meanings such as 'rugged rock', 'knife pattern' or 'broken blade'. The Parang design consists of slanting rows of thick knife-like segments running in parallel diagonal bands. Parang usually alternated with narrower bands in a darker contrasting color. These darker bands contain another design element, a line of lozenge-shaped motifs call mlinjon. There are many variations of this basic striped pattern with its elegant sweeping lines, with over forty parang designs recorded. The most famous is the 'Parang Rusak' which in its most classical form consisting of rows of softly folded parang. This motif also appears in media other than batik, including woodcarving and as ornamentation on gamelan musical instruments. longer dependent on traditional (natural) dyes, as chemical dyes can produce any color that they wish to achieve. Modern batik still utilizes canting and cap to create intricate designs.

longer dependent on traditional (natural) dyes, as chemical dyes can produce any color that they wish to achieve. Modern batik still utilizes canting and cap to create intricate designs. world that is dominated by machines there is an increasing interest in materials that have been handmade. Batik is one of these materials.

world that is dominated by machines there is an increasing interest in materials that have been handmade. Batik is one of these materials.